Monetary inflation is addictive both for governments and those who benefit from it. Once started, it is difficult to stop. Politicians and bankers may think that they are wiser this time not to repeat past mistake.

In this article, I just want to introduce Andrew D. White's book published in 1896 describing the economic experience of France in the latter part of 18th century. In reading the first 10 pages of the book, you will have an overview of France's situation at that time and how both the leaders and the people thought that they were wiser than John Law's generation.

Introducing Andrew D. White's ebook

Several days ago, I was thinking how I could use my time meaningfully particularly in my reading of Austrian economics. Among many topics, I selected to study the most researched one, inflation. And so I dug into the available literature provided by mises.org and came up with a list of more than a hundred ebooks in my bibliography. I started with Andrew D. White's Fiat Money Inflation in France: How it Came, What it Brought, and How it Ended.

White's ebook has only 79 pages, but summarizing the ideas contained in it is still too big to digest for an average reader. So I decided to summarize it in bite-sized portion. The ideas in this article are taken from pages 1 to 10. In reading the first ten pages of the booklet, you will see an overview of economic condition of France in the latter part of 18th century.

France in 1789

The year was 1789. Both the national leaders and the citizens of France were fully aware of the great dangers of increasing the money supply. The memory of economic ruin during John Law's era was still fresh in their mind. They still remembered the country's suffering about seventy years ago.

The nation's leaders knew that once the increase of paper money was issued, it is like using an addictive drug that's difficult to stop. They were totally informed about the disastrous consequences of monetary inflation. Nevertheless, they still pursued the easy path to economic recovery despite their knowledge that their action would result to long-term destruction of wealth, reduction of the purchasing power of those who depend on fixed salary, of the emergence of professional "thieves", "a class of debauched speculators" (p.1), of stimulation to overproduce, of industries' depression afterwards, of the breakdown in the habit of saving, and of the appearance of political and social immorality (pp. 5-6). The nation experienced all these bitter consequences of increasing the money supply. However, they thought they were wiser after such experience, and they would never repeat the same mistake. They were deceived.

So in 1790, the government issued the release of "four hundred millions of livres in paper money" (p. 7). Everybody was happy with the immediate results of the injection of new money into the total money supply. ". . . the treasury was at once greatly relieved; a portion of the public debt was paid; creditors were encouraged; credit revived; ordinary expenses were met, . . . trade increased and all difficulties seemed to vanish." (p. 10).

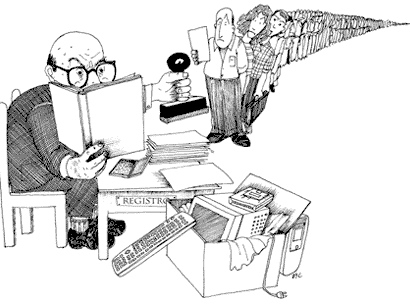

After five months of short-term celebration, economic uneasiness and distress reappeared. Instead of admitting that the issue of paper money five months earlier was a mistake, the French unanimously cried for another dosage of monetary inflation. The country was trapped, and it appeared that nothing could stop them down to the path of economic calamity.

Governments Never Learn

The information provided by White in his booklet deserves wider audience so that discerning readers would take necessary action to protect themselves from economic catastrophe that would certainly result from the determined action of governments to inflate their nations' money supply. This concise information teaches that not only France of 18th century failed to learn the painful lesson from John Law's generation; similar scenario is happening in our time.

Politicians and mainstream economists ignore the warning coming from the Austrian school. They think they are wiser this time, and they will never repeat the same mistake committed by the French.

Source:

White, A. D. (1896). Fiat money inflation in France: How it came, what it brought, and how it ended. New York: The Appleton and Company.